Meander Maps

Boney M is on repeat, I have consumed several barrels of mulled wine, it feels like good grief how are there still so many working days left, and it's dark at 4pm. In other words, it's beginning to feel a lot like Dezemba.

I'm racing to finish my novel by the end of the year, but finding time in-between to indulge in my favourite panic-procrastination activity: hyperfixating on obscure topics for 12-24 hours at a time, before never thinking about them again!

Thinking about maps

I spent a chunk of this June staying in a castle in rural France (don't hate me). The castle is so old that it has a moat, but over the centuries, the river that once fed it moved two-hundred metres away. Never fear, because the dry moat is now lush with stinging nettles: a superior line of defence!

A river feels like such a permanent thing, an immovable feature of the landscape. But even landscapes writhe and shift, given enough time.

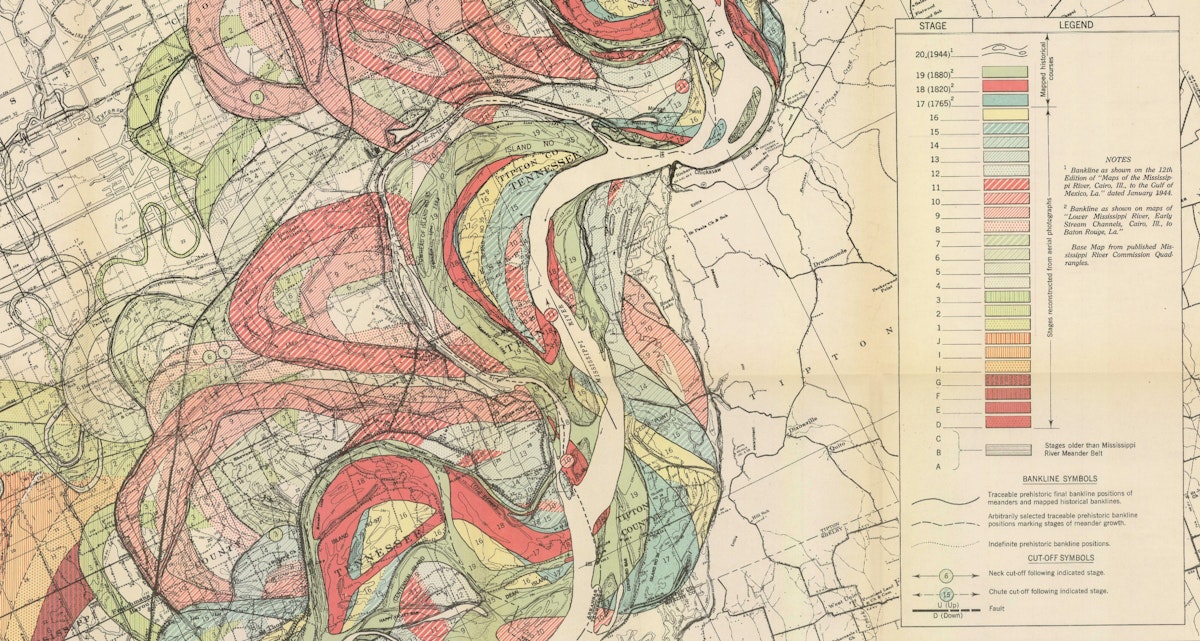

I've been recently fascinated by maps which attempt to capture change, like this gorgeous map series by cartographer Harold Fisk from 1944 which chart the shifting paths of the Mississippi River, its "meander belt".

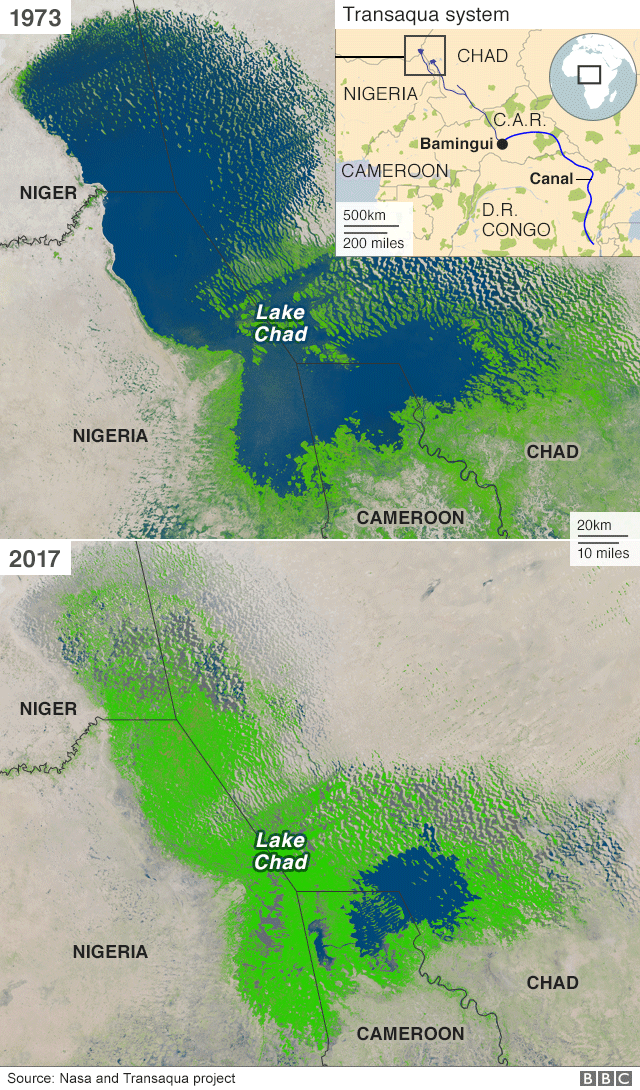

One of my favourite TikTokers (@jakie62) dates old globes, usually accurate to within a couple of months, by looking at political details like whether the Democratic Republic of Congo is called Zaire, or if the Soviet Union exists. As humans have an increasingly dramatic impact on our landscapes, it strikes me that we'll soon be able to date our maps by geophysical clues. For instance, you could look for Uunartoq Qeqertaq ("Warming Island" in English), an island in Greenland that was uncovered by the melting polar ice caps and officially added to the Times Atlas of the World in 2011.

You could check how big Lake Chad is - it shrank 90% between the 1960s and the 1990s.

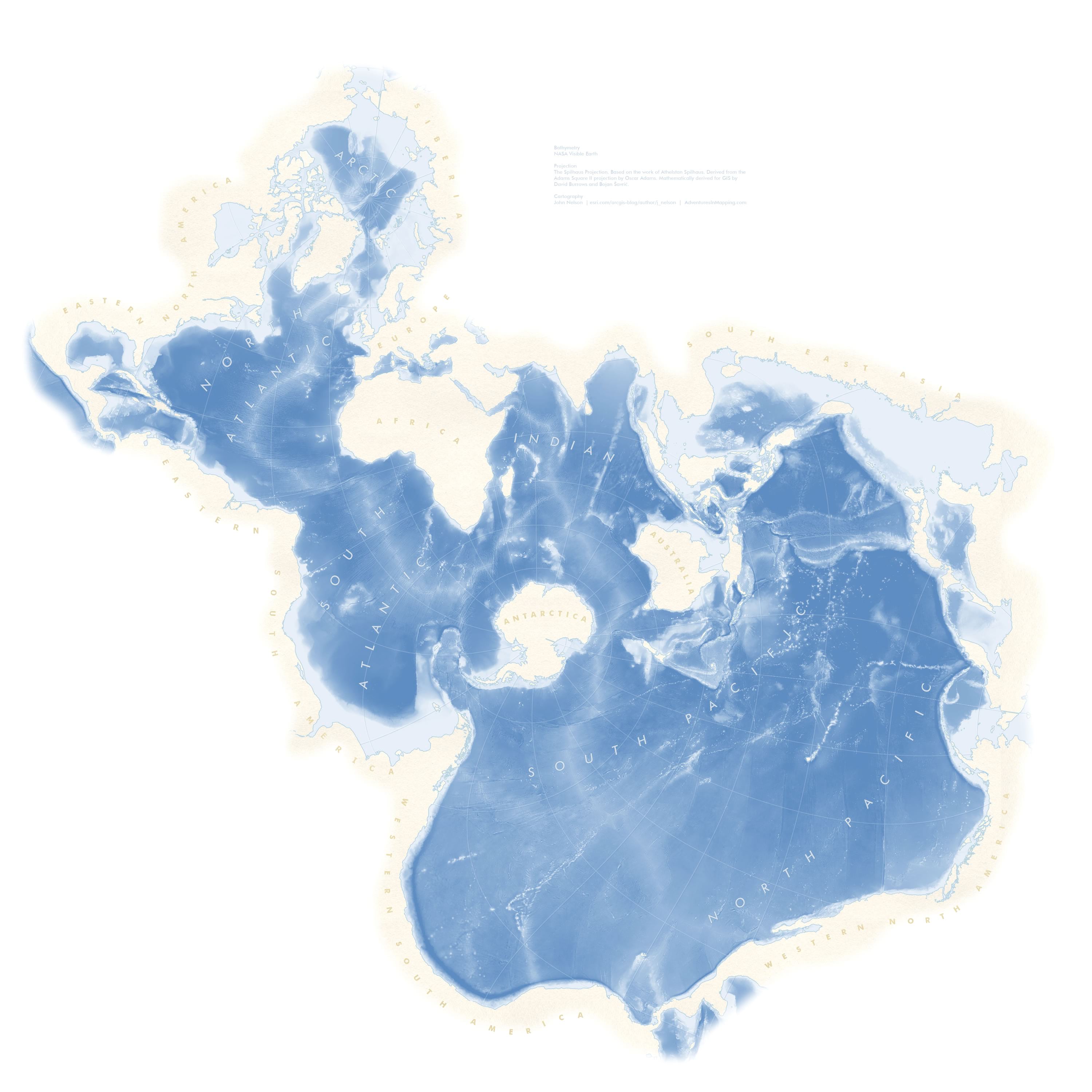

Maps can record change, but they can also upend our perspective. One last map I've been thinking about a lot recently is this 1942 one by South African-American oceanographer Athelstan Spilhaus. It's a map which centres the ocean rather than the land, or, as my dear friend Charne Lavery puts it (borrowing from Frans Blok), "how a penguin looks at the world". Listen to Charne being absurdly witty and brilliant about it on a 13-minute podcast here.

Thinking about insatiable appetites

Sneaking in under the wire to take its place as one of my favourite novels of the year is A. K. Blakemore's The Glutton: the reimagined story of a real-life 18th-century sideshow performer who could eat almost anything - corks, live eels, possibly babies.

The novel reminds me a little of Patrick Süskind's Perfume in how it skips a tightrope between the grotesque and poetic, deploying radiant prose to tell a sick story. It's obscene and deeply discomforting, but also profoundly moving and humane. Every single sentence is just so damn well-written it makes me want to throw my laptop into the river.

Bestie Lauren Beukes wrote a magnificent review of it for the New York Times, which begins:

You can’t trust poets. They feel too keenly for other people, are too ready to climb into the hearts and guts of things and lay them bare and bloody and obscenely beautiful in front of you. Even monsters. Maybe especially monsters.

Thinking about historical deepfakes

In the year 218 AD, a fourteen-year-old named Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (known as Elagabalus) became the emperor of the Roman Empire, which at that point stretched from Scotland to Egypt. Over his four-year reign, he did pretty much exactly what you would expect a fourteen-year-old emperor to do: spent his time throwing epic parties.

Here are just a few of the many wild stories about Elegabalus.

- He often served 22-course meals including peacock heads, flamingo brains and rice with pearls.

- He had pet lions and leopards that would cuddle up with guests after meals.

- He invented the whoopie cushion.

- His pet dogs lived on foie gras.

- As party favours, he'd give out carriages.

- He had couches of solid silver made for his banqueting-rooms.

- He never wore the same pair of shoes twice, insisting on a new pair each morning.

- He made major political decisions by drinking match.

- He (she?) might have been a trans woman, asking people to refer to her by feminine pronouns, dressing as a woman and marrying her male charioteer, leading some contemporary writers to reclaim Elagabalus as a queer icon.

- He once ordered so many rose petals to shower over his guests at a party that he accidentally smothered them to death (depicted in the painting above).

A true icon, am I right?

Only... sorry, but none of these things likely happened!

The problem with trying to learn anything about famous people in history, especially those who were assassinated (as Elagabalus was), is that their biographies were usually written by people who had a vested interest in making them seem terrible (thereby excusing the fact that they were murdered). Elagabalus suffered worse than most because he was Syrian, an outsider who worshipped a non-Roman god. Most of these tales about him were inventions designed to curry favour with his successor on the throne.

I had the privilege of listening to classicist Mary Beard talking to David Mitchell about this last week (gotta love how much nerdy shit there is to do in London).

The toolkit with which people have constructed an image of their rulers, judged them, debated the character of an autocrat's power and marked the distance between "them" and "us" has always included fantasy, gossip, slander and urban myth. (Mary Beard)

It's interesting to realise that some of the most lurid (and fun) stories from history are probably untrue, but it's also interesting to think about what the lies themselves tell us about society at the time, what behaviour would have been considered sordid and monstrous, and what that reveals about the anxieties the Romans had about their autocratic rulers.

I also enjoyed Beard's sassy response to the question, "Why do you think men spend so much time thinking about the Roman Empire?", which was (I'm paraphrasing), "Generalising... men like to imagine conquering things, and the Roman Empire is the last acceptable face of fascism."

Read more about this in Mary Beard's accessible and delightful new book, Emperor of Rome.

Thinking about dying empty

I recently came across this lovely quote about writing by Annie Dillard, which I think applies to all of our most meaningful work:

One of the few things I know about writing is this: spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water.

Thinking about financial infidelity

A request for help, dear readers! I'm writing a piece for Fairlady about financial infidelity, and I'm looking to interview people who discovered that their partner or spouse lied to them about money. Do you have a story about secret debts, uncontrolled spending, credit cards taken out in your name, an investment that didn't exist, assets hidden during a divorce, or outright fraud? I'd love to talk to you.

Anything you share with me will be treated with utmost care and confidentiality, and will be reported anonymously. If you're happy to chat, just hit reply.

This is probably the last newsletter for the year, friends, so until the new year, I'm wishing you parties worthy of Elagabalus, and time with your loved ones.

Sam

Member discussion